This is a good story, so I typed it in.

Excerpted from:

U-Boats Offshore: When Hitler Struck America

Chapter 25

"God Bless the Commonwealth of Massachusetts..."

or

"Red Cross vs. MCPS"

The quarreling, the errors, the duplications, and the misunderstandings that hampered American defenses were not confined to the military. They seemed to permeate the whole American effort along the shore.

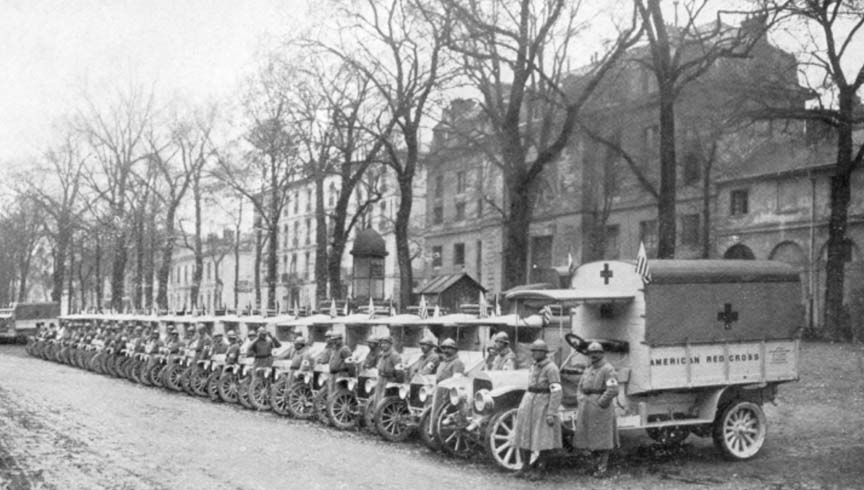

For many months, the American Red Cross had been performing admirably in assistance to military authorities in the care and treatment of merchant seamen.

In April, when the survivors of the S.S. City of New York had been brought to Norfolk, by the destroyer Roper,the Red Cross took over.

Mrs Desanka Noharovic and her new "lifeboat" baby were taken to St. Vincent;s Hospital, along with other sick and injured.

The Red Cross supplied clothing, transportation, razors, and toothbrushes. Dr, Albert Crosby, chairman of the Norfolk, chapter, even appeared at the hotel to which some survivors were taken to treat them for minor ailments.

In Norfolk, the Red Cross arranged for a myriad of services; one man had his glasses repaired, and the gray ladies made appointments with the hotel beauty shop "to fix the women's hair."

The ambulance corps and the nurses' aides pitched in with everything from books and candy to morale-raising alcohol rubs.

That Norfolk story represented a typical Red Cross performance; in these port cities, the organization had been at the work for two and a half years already, since the day that Hitler marched into Poland. They did the job without seeking attention or thanks.

The increasing tempo of the war along the American coast brought new pressures. In May, for example, the Key West Red Cross cared for survivors from 14 different ships sunk by submarines in southern waters.

Somehow the Red Cross always seem able to cope. They cared for the badly burned men of the Mexican tanker Faja de Ora, whose 27 survivors landed at Key West. They helped the burned, half-drowned men of Samuel Q. Brown, and when one of the young boys died of his burns in the Marine Hospital, the Red Cross provided the $111 needed to send his body to Princeton for burial.

They managed in shortages and the heavy outlay of money that had to be made at the expense of the volunteers until the Washington headquarters could get around to reimbursements.

They made friends almost immediately with Naval Intelligence, which found the Red Cross useful in a dozen ways.

But in the broadening of the war, soon the Red Cross was not alone among civilian assistance organizations.

The Office of Civilian Defense came into being, and it spread its tentacles in to the states.

Its local organization in Massachusetts, was the Massachusetts Committee on Public Safety (MCPS).

On Cape Cod, the new committee was industrious and very eager to participate in the war.

With the increase in sinkings in the spring of 1942, more survivors began to come ashore, and in spite of the new government policy of suppressing much of the news, the word got around by word of mouth.

In May, Aaroon Davis, regional director of MCPS in Hyannis, fretted over the priority given the Red Cross when his organization was ready and willing to do everything needful for survivors of torpedoed ships.

Davis decided to do something about it. He Paid a call on Lieutenant Ireland of the Coast Guard station at Provincetown. He complained that when survivors were brought in , the authorities always called the Red Cross. He wanted them to call the committee, too.

He Paid a call on Lieutenant Ireland of the Coast Guard station at Provincetown. He complained that when survivors were brought in , the authorities always called the Red Cross. He wanted them to call the committee, too.

Lieutenant Ireland agreed that next time around he would inform the committee as well as the Red Cross.

He was as good as his word. On Tuesday, June 16, survivors of the torpedoed transport S.S Cherokee were being brought to shore by S.S Noriago and P. G. San Bernardino.

Cherokee had been hit 46 miles off Cape Cod light - the Germans were in that close - and she had gone down fast, taking nearly 200 men with her. The survivors might come to the Cape Cod Canal. They might come to Provincetown.

When the call came just after 6:30 in the morning, the war-wise Red Cross volunteers got ready to do the jobs they did best: provide canteen service, clothing, and transportation fo the stricken men.

When the call came to John Rosenthal, Provincetown chairman of MCPS at 6:45, he swung into action. Lieutenant Ireland said he did not know the exact number of survivors. He also asked that the news be kept from the public in the national interest, and Rosenthal listened carefully. Then he got on the telephone.

He called his chief air raid warden and the deputy chief air raid warden, the chief of auxiliary police, the chairman of the First Aider, the head of the medical department, and Drs. Cass, Heibert, Perry and Corea of Truro.

They all stood by for further orders.

He summoned the head of ambulances to the Report Center, and the head of ambulances and all the others telephoned the workers in their units to stand by. At 7:30, Rosenthal had at his disposal seven ambulances with drivers, four first-aid workers with each ambulance, and Mrs. Comee and Mr. Law of the Red Cross. Rosenthal made sure all the equipment was parked behind the post office "so that the public would not know about the same."

At 7:30, Rosenthal had at his disposal seven ambulances with drivers, four first-aid workers with each ambulance, and Mrs. Comee and Mr. Law of the Red Cross. Rosenthal made sure all the equipment was parked behind the post office "so that the public would not know about the same."

Rosenthal then kept summoning workers. Mrs. Baumgardner, the head of the canteen, came to headquarters. She waited with the rest. Rosenthal had another call from Lieutenant Ireland. It was definitely Provincetown, not the Cape Cod Canal. The lieutenant still did not know how many survivors there would be.

Chairman Rosenthal dispatched his chief air raid warden to see Mr. Cashman, the manager of the Town House, a local hotel, and to take it over as a refuge for survivors. If Cashman did not want to cooperate, Chairman Rosenthal said, the chief warden was to tell him that Chairman Rosenthal would take it over, anyhow. The display of power was unnecessary. Manager Cahman said he would be glad to let them use his hotel.

Rosenthal then dispatched Mrs Baumgardner and her 25 canteen workers to Town House along with Mr. Marshall, the chairman of food supplies. They took over the kitchen of the hotel and the dining room and "immediately started on food supplies." Graciously, they accepted the assistance of Mr. Law of the Red Cross. He delivered the food.

At eight o'clock, Deputy Chief Air Raid Warden Pigeon was placed in charge of the Report Center because Mr. Rosenthal had important things to do.

The rescue ship was coming in!

There was no danger in leaving his post. Pigeon was there in charge, and he had seven telephone operators standing by for orders, as well as two Boy Scout messengers.

Dr Hiebert, who was also public health officer, went out in a Coast Gard boat to board the ship. Dr. Cass, who was chairman of the medical division, stood by to await Mr. Rosenthal's orders, which would be transmitted at the Report Center by Pigeon - Warden Pigeon.

Dr. Perry and Dr. Corea were sent to the Town House to stand by with five registered nurses and four first aiders.

Chairman Rosenthal took Chief Air Raid Warden Hallett to Lieutenant Ireland's office on the end of the town pier. The chairman used the telephone there to check in with the Report Center and the Town House. They were standing by.

The radio crackled. The survivors had been taken off the ship Noriego and were being brought into Provincetown. Immediately, Chairman Rosenthal was on the telephone. He ordered Dr. Cass and the ambulances to leave the Report Center and come to the town pier.

Dr. Cass and his ambulances arrived almost immediately, and Cass was dispatched to the Noriago by Coast Guard boat to help Dr. Hiebert.

From the Report Center, Deputy Chief Air Raid Warden Pigeon had been summoning the flock, and by nine o'clock the entire auxiliary police department of 50 officers was on duty. Main Street was roped off from the town pier to the Town House, all traffic was diverted, and when the first boatload of survivors arrived, they were rushed into the ambulances and hurried the little way to the Town House where Dr. Perry and Dr. Corea and now assembled 5 registered nurses, 4 first aiders, and 35 home nurses to help them.

By this time, Chairman Rosenthal had learned that there were 44 survivors, including two hospital cases. "We served coffee," he said, "and the Red Cross had on hand a supply of dry clothing."

"We served coffee," he said, "and the Red Cross had on hand a supply of dry clothing."

The doctors examined the survivors. Fourteen were suffering from shock or had suffered minor injuries. They were assigned to beds. They had the services of two doctors, 5 registered nurses, 4 first aiders, 35 home nurses, and now Chairman Rosenthal assigned 4 air raid wardens to serve as male orderlies. Never let it be said that Massachusetts did not know how to take care of its guests.

Since the Town House was the place of action, the seven public safety telephone operators were hurried there.They displaced the Town House operators, and Mr. Gott, the district manager of the New England Telephone Company, soon had the hotel switchboard hooked up so the seven public safety operators could control it.

Chairman Rosenthal put his people on watches: three hours on, three hours off until further notice.

At 11 o'clock the second boat-load of survivors arrived, and the people were hustled to the Town House.

It was midmorning, and Provincetown was wide awake. People were beginning to wonder what all the excitement was about. Chairman Rosenthal assigned a number of his auxiliary police to guarrd duty around the Town House. Only "authorized" persons were to be admitted, and the authorization would come from Chairman Rosenthal.

Other auxiliary policemen stood inside on guard to be sure the survivors did not give out any information to anybody - not even the public safety workers.

Just before noon, the last two survivors arrived. They were the hospital cases. The seven public safety operators dispatched them to the Boston Marine Hospital. He sent a first aider and an auxiliary policeman along with the driver and ambulance orderly to see that the injured survivors did not tell anybody anything. Chairman Rosenthal was as conscious of the need for security as anyone.

All this while the chairman had maintained his command post in the Coast Guard office at the end of the pier. From time to time, he and Chief Air Raid Warden Hallett made several trips back to the Town House to check on operations. They were going very well. They were going so well, in fact, that he could not use all the new first aiders and public safety workers who began to turn up to help.

The Red Cross had supplied magazines, playing cards, games, cigarettes, and candy, and "from then on first aiders, home nurses, and canteen workers that could be spared performed a marvelous job of helping to keep the morale of the survivors up, by playing cards, checkers, etc, with the men, taking their minds from their recent experiences," said Chairman Rosenthal's report.

In the early afternoon, three officers from Naval Intelligence arrived, along with an officer from Army Intelligence. Chairman Rosenthal assigned them a private office in the hotel. Lieutenant Ireland was also allowed to use it.

As evening approached, the Town House livened up. The canteen workers moved about dispensing orange juice, hot coffee, oranges, candy, and cigarettes; the 45 first aidersand 35 home nurses played cards and checkers and talked brightly to keep up morale. The 42 survivors were having a wonderful time.

Early in the evening, two army ambulances and an army truck appeared, and the officer in charge ordered out the soldiers in the group. It was hard for them to leave.

They all said what a fine rescue it had been, and the senior sargeant made a little speech. He said that although he had spent his lifetime in the army and had traveled all over the world, he had never received such hospitality as he had from the MCPS at the Town House in Provincetown. Everyone was sorry to see the soldiers go.

Mrs. Baumgardner, in charge of 27 canteen workers, had by this time been on the alert since seven o'clock in the morning. Chairman Rosenthal suggested that she go home.

Mrs Baumgargner was obdurate. Go home? She knew where she was needed. She refused to be relieved, and so did her trusted workers. They would labor into the night for the rescued.

That evening, Red Cross Disaster Chairman Howard Hinckley came down from the Hyannis office of the Red Cross with three other Red Cross workers, bringing more clothing for the survivors. It was gratefully accepted. But what was happening at Provicetown was the MCPS show, not the Red Cross's. That was made very clear to Hinckley.

At eleven o'clock that night, Chairman Rosenthal was still going strong. A mine sweeper arrived at the pier, carrying the bodies of two soldiers it had picked up after the sinking of the Cherokee.Chairman Rosenthal accompanied army, navy, and Coast Guard officers to the pier and made arrangements for local undertakers to handle the bodies.

While they were on the pier came more disastrous new. A naval vessel was headed into port with 40 more bodies. Chairman Rosenthal got on the telephone. He called the mayor and made arrangements to use the town hall as a morgue. He called more undertakers, in Wellfleet and Orleans, and they hastened to the scene. The chairman assembled his air raid wardens and auxiliary police and ambulance drivers.

In half an hour, on the pier were ten ambulances and trucks, each with air raid wardens detailed as stretcher bearers. Chairman Rosenthal told them to stand by for further orders.

They stood by until midnight, then until one o'clock on Wednesday morning. At 1:30 came the word: the vessel would not come in because of fog. She would be dispatched to another port.

On Wednesday morning, Chairman Rosenthal had to call on the Red Cross once more, for he needed a special bus to pick the merchant seaman and take them to the Boston Seaman's Institute. The Red Cross responded immediately. The bus arrived at ten o'clock with a state police escort.

As the survivors came out to get on the bus, most of the public safety workers came out to bid them farewell.

"Many of the survivors, with tears streaming down their cheeks, remarked that they hoped some day to get back here again to renew their acquaintances, and all expressed their heartfelt appreciation of the kind and friendly treatment they had received," the chairman's report said.

The bus doors closed, everyone waved, and the state police escort led the survivors away on the road to Boston.

At 2:30 that afternoon, the last bit of scrub-up was finished, and the Town House was returned to the management of Mr. Cashman. The hotel operators got thier switchboard back. The 4 doctors, 5 registered nurses, 5 orderlies, 45 first aiders, 35 home nurses, 27 canteen workers, 7 telephone operators, 4 Boy Scout messengers, 4 ambulance drivers, 50 auxiliary police, 25 air raid wardens and 20 members of the staff went home.

Chairman Rosenthal ave credit where credit was due. Mrs. Baumgardner, he was quick to point out, had not closed her eyes or rested from seven o'clock Tuesday morning until after 2:30 on Wednesday afternoon. Modestly, he said nothing about his own labors during the long vigil, and two days later, when he wrote his report, he was lavish with his praise of all concerned. Cmdr A. D. Turnbull, the first chairman, he said, deserved much of the credit for his thorough job of organizing.

It had been a major operation.

During the 32 hours after the MCPS pre-empted the Town House, the canteen workers served 500 meals, 1,000 cups of coffee, and 250 sandwiches, plus quantities of fruit juice, oranges, candy, and custard. Food had come into the kitchen from all over the community. The Red Cross had contributed heavily. So apparently had the Town House, for when the party was over, the total canteen bill submitted by Chairman Rosenthal was only $40.

Chairman Rosenthal was well pleased; Naval Intelligence, the captains of the two ships he had met, the Coast Guard, had all commended him for the fine job done by his workers.

He wrote out his report carefully, not forgetting to use both sides of each sheet. ("Paper must be conserved as a war necessity...please turn this sheet.") Then he sealed it up and sent it off to Aaron Davis, director of Region 7.

David read and admired what he read.

In a military manner, using the last unfinished sheet of Chairman Rosenthal's Report, he endorsed it and sent it on to Boston headquarters.

"I can add no word to this.

"God bless the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

"It should be proud of its Committee on Public Safety."

The report was sent to J. W. Farley, executive director of the MCPS. On June 25, the report was given to the Boston newspapers, and it was printed verbatim by the Boston Globe.

The Red Cross was furious.

William H. G. Giblin, director of Disaster Relief Service for the North Atlantic Area reported to his Washington office that the Red Cross had, as usual, been on hand, ready to supply canteen service, clothing, shelter, and transportation.

The Red Cross people learned that Chairman Rosenthal and his workers had commandeered the Town House. They were shut out in the cold. They provided the canteen service and the clothing and all their usual supplies. The workers took them over.

They provided the food. The workers took it, and everybody ate it.

What infuriated the Red Cross most was the report in the Boston newspapers.

"From reading the report the casual reader would fail to understand that most of the work was rendered by the Red Cross but would infer that the Red Cross only supplied certain supplementary service on a very small scale."

It was not just Gliblin's pique working. The repercussions all through New England were serious: Many chapters began to question their viability. Was the Red Cross still the responsible agency for the care of survivors of the disasters of the sea?

The question could not be answered immediately by the authorities that counted, the naval commands. And the MCPS was riding high.

On Friday, July 3, at 8:30 in the evening, the Hyannis Red Cross office had a call from the Coast Guard to inform them that some time after ten o'clock 31 victims of a torpedoed ship would arrive at Woods Hole Navy Yard.

The request was routine: cots, blankets, and clothing. The Red Cross made routine of filling it as it had done so many times before.

Frank Holmes, the general field representative, set out for Woods Hole, and there met Howard Hinckley, the disaster chairman, and Milfred Lawrence, his assistant.

Hinckley and Lawrence were very angry. The MCPS was moving in on them again.

Hinckley said that he had a call from the Falmouth chairman of the MCPS, demanding the cots and blankets to be turned over to them because the committee did not have any.

And when the Red Cross men arrived at the scene, the safety committee chairman was there, with 150 workers, an ambulance corps, a canteen, taking over again.

Aaron Davis was in charge himself this time. He scurried about making arrangements. He arranged for ten MCPS workers and two Red Cross people, Hinckley and Lawrence. He had made no arrangements for Frank Holmes, and he told the field representative that he could not have a pass to the navy yard.

Holmes did not say a word. He turned on his heel and headed for Coast Guard headquarters. There he conferred with Lieutenant Whitmore, the commander of the unit. The lieutenant gave him a pass without hesitation, and Holmes went into the yard to confer with the naval authorities in charge of rescue and survivors.

They told him that the rescue ship had just radioed that it would not arrive until morning because of heavy weather.

So the Red Cross men left their telephone numbers and went home. Outside the base, Director Davis dismissed his workers, and they went home, too.

Holmes and Lawrence returned to the navy yard on Saturday morning. This time there were no MCPS workers in sight.

They waited.

At three o'clock in the afternoon, the word came. The ship would arrive in half an hour. When the survivors came in, the Red Cross was there, with clothing and under-clothing, money, and comfort, Three of the men had escaped stark naked and needed everything supplied for them.

The ship's captain was among them, and he asked the Red Cross to supply transportation to New York, which was done. The Cape Cod Motor Corps was rallied and took the men to Providence in cars and station wagons, where they were put on the train to New York City, with tickets purchased by the Red Cross. The Red Cross gave the money to buy meals for the men on the train.

The Red Cross men went back to the Naval Intelligence office then, and there Lieutenant Good, the officer in charge, remarked on the disgusting display of Aaron Davis and his workers at Woods Hole and at Provincetown. In the future, he said, the local Navy Yard, at least, was going to call only the Red Cross.

In Hyannis, Aaron Davis fretted. He complained to higher authority in the MCPS in Boston.

In July, Joseph Loughlin of the U.S. Office of Civil Defense called a meeting in Boston to try to iron out all the difficulties. After the commotion in June, Loughlin felt it necessary to clear the air so thee MCPS could take over its proper responsibilities for aid to victims of war disaster without Red Cross interference.

Loughlin invited representatives of the army, navy, and Coast Guard to a meeting. The list included 16 admirals, generals, captains and colonels, a number of Civil Defense officials from Massachusetts and Washington, and one representative of the Red Cross, Charlies Gates, director of the Massachusetts emergency field office.

When the room was quiet, Loughlin handed around a prepared memorandum that "proved" that the civil defense office was entitled to the responsibility and authority to handle all victims of the war offshore. Then his assistants began to improve on the case orally.

The head of the medical division of the MCPS pointed out how good the medical division was.

An official of the Social Security agency up from Washington explained how important Social Security was.

Other officials of the MCPS explained their operations and proved once again that theirs was the proper organization to handle these matters.

After about an hour, a Lieutenant Wilson of the Coast Guard leaned over to Gates.

"You're with the Red Cross?"

"Yes."

"What the hell is the idea of all this? Isn't the Red Cross doing its job?"

"Yes. But apparently some other people want the job."

The meeting lasted another hour. Loughlin had expected it all to be settled here, but the admirals, generals, captains, colonels, and Lieutenant Wilson were not convinced. Charles Gates suggested that the Red Cross was doing just fine.

The issue was not resolved; the meeting broke up in exhaustion.

Finally the quarrel had to be taken to Washington. Admiral Waesche of the Coast Guard, Admiral Land of the Maritime Commission, and DeWitt Smith, director of domestic operations for the Red Cross argued the case with Paul McNutt, federal security administrator, and with representatives of the Office of Civilian Defense.

The navy and commission representatives told the civilians to leave the Red Cross alone.

And only then did the MCPS subside and let the Red Cross get back to its job.

No comments:

Post a Comment